Futurecity Curator Chloe Stagaman spoke with Manijeh Verghese and Madeleine Kessler, Co-Curators of the British Pavilion at the 17thInternational Exhibition of Architecture in Venice (22 May— 21 November, 2021) and Co-Founders of UNSCENE Architecture, a practice that works with local communities to empower ownership and greater agency over how they use and occupy their spaces.

CS: How did you decide upon the title and concept of The Garden of Privatised Delights exhibition for the British Pavilion at the 17thInternational Exhibition of Architecture in Venice?

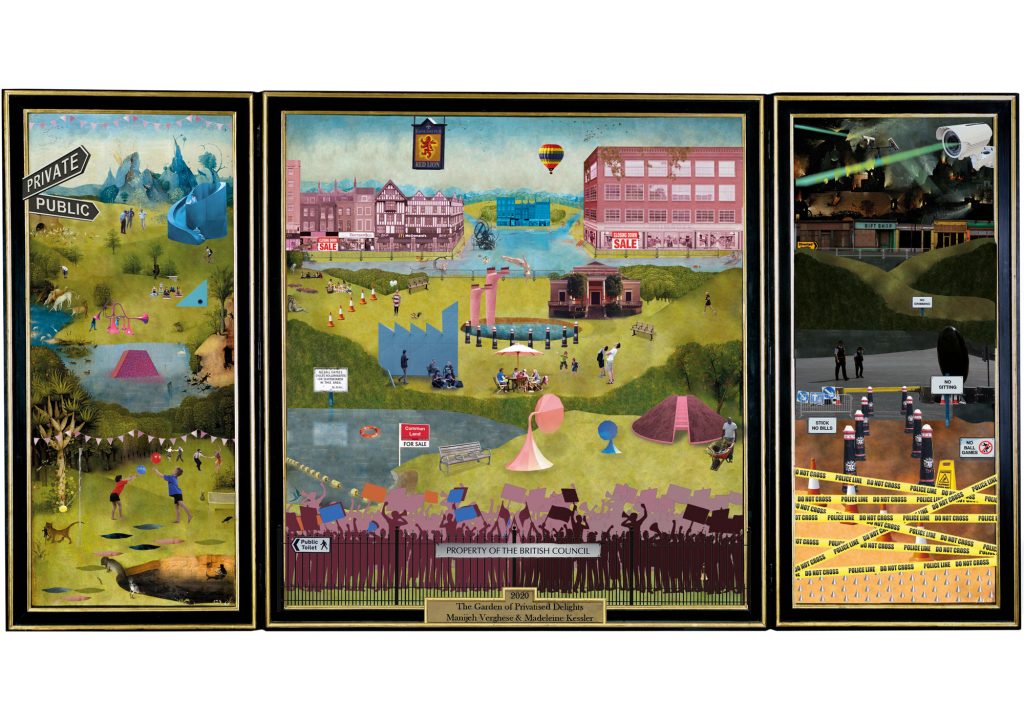

MV: The title of the exhibition is inspired by the painting The Garden of Earthly Delights by Dutch artist Hieronymus Bosch. The painting depicts a surreal atmosphere replete with incredible activity and imaginative architecture. Its triptych composition frames the middle ground of earth between heaven and hell representing the gradient between two extremes. We translated this into a conceptual collage of our interpretation – The Garden of Privatised Delights that looks at privatised public space as a middle ground between the extremes of the utopia of common land before the enclosure acts of the 18th Century and the dystopia of total privatisation.

We are also interested in how the pavilion can become a platform to discuss important research projects like Guy Shrubsole and Anna Powell-Smith’s Who Owns England? mapping project that looks at how the government has been selling off public land to private buyers unbeknownst to the public for decades, and aims to provide greater transparency around land ownership.

You don’t have to be an architect or designer to engage with the exhibition or contribute to the conversation. The topic engages the public, empowers them and gives them agency to understand these spaces. It is meant to give the public tools to occupy and change their spaces.

MK: The Garden of Privatised Delights looks at how we can better open up privatised public space, proposing strategies for more inclusive ownership, access and use. We have been interested in privatised public space for a number of years, coming together to explore this topic through research, teaching and practice. In 2015 we taught a Summer School at the Architectural Association investigating the use of the pub as everything from a living room to the modern-day public toilet. Out of this we began exploring privatised public space as not just paved squares in new developments but as a series of typologies embedded in British culture, such as the garden square, the High Street and the pub. Our project highlights the threats to public space, proposing new ideas for ownership, access and use.

Our ability to access or use privatised public space impacts everyone’s experience of a place or a city. We are interested in how the architect is not just someone who designs and builds, but is also a communicator and facilitator of conversations that bring people together. Our aim with the British Pavilion is to not just to create an exhibition for architects, but an exhibition that everyone can engage with. The exhibition subsequently takes the form of a series of immersive experiences for visitors to interact with. Spaces under threat like the youth centre, and inaccessible enclaves like the garden square, are overlaid with proposals for how they can be reprogrammed and revitalised. We also think it’s important to consider legislation alongside design, and two of the spaces explore new government ministries, looking at the ownership of Land and Data. Each room is designed in collaboration with a room designer who is exploring these themes in their work, including the Decorators, Built Works, Studio Polpo, Public Works and vPPR.

CS: Which came first, The Garden of Privatised Delights, or the platform you co-founded together called UNSCENE Architecture?

MV: While we have collaborated on teaching workshops and summer schools over the years, winning the pavilion competition was a catalyst for us to formalise our collaboration and set up Unscene. We always imagined the pavilion as a platform for a wider project. The audience for the Biennale is primarily architects so we want to see how the exhibition and its ideas can return to the UK and be tested in a variety of privately owned public spaces. We have realised that architects can be amazing advocates for public space, with the ability to push for transparency and encourage greater access. There is more we feel we can do to raise awareness and allow more people to participate in the conversation around privatised public space whether its at a policy, urban. Architectural or human scale through a series of curatorial and cultural projects.

MK: We’re interested in communities of all age groups, ranging from young people to the elderly. We want to work with people to understand what it is we can provide and do together. Manijeh and I have run a series of workshops for the National Saturday Club Trust over the past few years with 14–16-year-olds, helping them understand the city in new ways and think about becoming an architect. Our aim is to ensure that all voices are heard, seen and appreciated both in this project and in the city at large.

CS: How have UNSCENE Architecture’s aims evolved or enhanced in 2020 as COVID-19 has further unveiled vulnerabilities to exterior and even interior public spaces?

MK: We are in a unique time where people are both getting to know their neighbours and their neighbourhoods in a whole new way. People are starting to come together in new ways to test different ways of using their local space and how it can accommodate different activities and uses. We want to empower people to do more of that, and take ownership of their public space, reminding them that actually, as a citizen, they have huge power and say over what happens around them in their spaces.

MV: Through the pavilion, we have been able to have several interesting conversations with stakeholders in public space. Recently we attended a meeting organised by the Mayor of London’s Office (GLA) to discuss the impact of Covid-19 and the changes needed to improve public and privatised public space. It was interesting to observe that it takes a crisis to realise how agile you can be as a community.

MK: Over the past few decades we have seen an increasingly risk-adverse attitude. With COVID we have started to see a shift and a sense that it’s important to test different ways of using space in our cities to allow our neighbourhoods to evolve. There is a renewed appreciation on the importance of our cities being designed by and for people. How can we give the public a greater sense of ownership so that they can inhabit their public spaces and encourage certain activities within them?

CS: UNSCENE Architecture aims ‘to provoke a wider conversation about the city through action rather than just words.’ What does that action look like today? What do you hope its legacy will be?

MV: It is easy to problematise privately-owned public space, but how do you actually get involved and transform words into action? For example, the railings around garden squares could be removed and these spaces opened up to everyone. We feel a lot of the actions are simple, with a long term impact on their surrounding communities. We would like to initiate conversations with landowners who generate income through hiring out these gated squares or keeping them private for residents to see how we can find a compromise to open them up strategically for a local community and meet their needs. We are interested in the role of the architect as a facilitator of these conversations but also how we can design better public spaces as ‘Gardens of Delight’.

MK: These are all conversations we’ve started to have over the past year and are looking forward to testing and evolving in the months and years to come. We are interested in how the architect is not just someone who designs and builds, but is also a communicator and facilitator of conversations that bring people together. In the evolution of the project, we have made a conscious effort to speak to those from outside our industry, including politicians, policy makers, developers, activists, community groups, young people and the elderly. The need for more inclusive public spaces is greater now than ever before. How can we bring everyone around a single table to have a conversation?

CS: What does the inclusive public space of the future look like?

MK: The public space of the future should be accessible to everyone. At the moment there are many barriers to entry – whether it be physical or intangible. Our hope is to bring people together to achieve more community-owned and community-led spaces that relate to local contexts.

MV: Flexibility is really important. Typologies like the pub or the high street were already under threat before Covid-19, but the current situation has highlighted these inequalities. Society has evolved and pigeonholed the usage of these spaces, labelling the pub as a space only for drinking or the high street all about retail. By cross-programming these spaces, they would become accessible to different groups for a range of uses and therefore not reliant on a single activity or source of funding. There could be more of a focus on local needs to design these spaces as specific to a community, which is where the role of the architect in translating needs into spaces becomes important. There are current examples of community-owned pubs that become spaces for marginalised groups and that can accommodate different programmes at different times of day. That is the future.

Read more about Futurecity’s Projects in the Public Realm and Community & Consultation.